Ten Years of Making Unconventional Career Decisions & Starting A New Public Health Journey (Revisited)

Looking back on ten years of an unconventional career decision.

Note: This post was originally published on May 5, 2022, on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of choosing a career in public health. With the relaunching of Scepticemia, I’m revisiting and updating this reflection with some of what has transpired since. This includes getting a PhD, continued work on global health pedagogy, and ongoing research into antimicrobial resistance and neglected tropical diseases through a decolonial lens. The core message remains as relevant today as it was three years ago.

Ten years ago, to this day, much to the consternation and befuddlement of some of my friends and well-wishers, I chose to pursue my MD training in Preventive and Social Medicine, ahead of more conventional career pathways in surgery, anesthesia, or other clinical subjects. Since then, I have wondered many times, what the counterfactual would look like… but, on reflecting on my eclectic, meandering pathways over the years, I cannot say I have too many regrets with the road I chose to traverse. After all, I have always been a bit of a gadfly, so why be anything else when it came to choosing career trajectories?

Looking back, there are so many things in life that have been linked to this career decision that I am eternally grateful for. Prime amongst them has been the privilege to meet my significant other, with whom I would have never connected had it not been for my career choice. There are so many friendships and associations that would not have blossomed but for this decision. I seriously doubt if I would have been able to train at the world’s premier institute had it not been for this career choice. I would not have been able to indulge the inner infectious diseases nerd in me, work in close approximation with the highest levels of policymaking in the nation, work on research projects that changed policies, and learn a million and one lessons about life, the world, and the universe.

When I was a somewhat lost MD student in my twenties, grappling with whether I had made a terrible mistake, I could hardly have imagined where this path would take me. But I can trace a thread running through these years: an almost relentless conviction that the most pressing health problems facing our nation, our world, required not clinical brilliance in the clinic, but rigorous thinking about systems, societies, and the structural forces that shape who gets sick and who gets well.

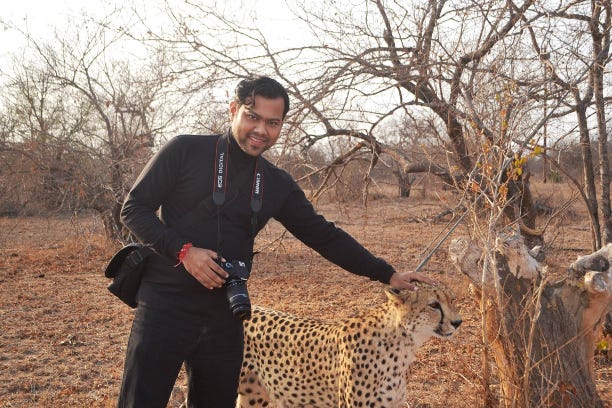

During my time at the Public Health Foundation of India, I was first exposed to the One Health framework, an approach that recognizes the deeply interconnected nature of human, animal, and environmental health. This was revelatory. At PHFI, I spent my time trying to understand the epidemiology of zoonotic spread of brucellosis and bovine tuberculosis across rural and peri-urban India, and suddenly I had a conceptual framework that made sense of the messiness I was observing on the ground. Animals in cramped conditions were fed antibiotics for growth promotion. Farmers handling infected livestock without protective equipment were getting sick. Wastewater from pharmaceutical manufacturing was contaminating local water sources. These were not separate problems requiring separate solutions: they were threads in the same fabric.

By 2017, when I joined the Indian Council of Medical Research’s National Institute of Cholera and Enteric Diseases in Kolkata (which has been renamed as National Institute of Research in Bacterial Infections – NIRBI), I had begun to develop a real understanding of how antimicrobial resistance unfolds across populations, across sectors, and across borders.

Sometimes, I indulge in wondering what I would tell my ten-year younger self, were I to talk to him today. And then I wonder, given how hard-headed I am, would I have listened to the (surely) cynical advice grizzled old me would be giving out? I would have perhaps used some of the time I whiled away a little better. Invested in learning some of the core skills areas that I am still struggling with. Played the “game” a little more carefully, taking care to be a little less cavalier about ticking people off (or not!). I am immensely grateful to be standing where I am today, and I realize that this is a sum total of all the decisions I made, all the right choices, the wrong choices, the choices never made, and the choices that were ignored. Each and every one of these steps has taken me towards becoming the person and professional that I am today. I must say that I am all the more enriched for it.

Knowing what I do about the futility of a large proportion of my MD training, I sometimes debate if I still would make the same career choice were I to go back in time and redo this decision. Given how public health and clinical medicine are divergent career choices, it is entirely possible that had I chosen a different career pathway, I would not have arrived at this junction today. Also, given that public health skills are not the forte of Preventive and Social Medicine graduates only, it is also possible that I could have retrained myself, and found a very different niche in this professional space.

Given my personal, political, moral, and policy convictions, one thing that is clear to me is that whatever career pathway I had chosen ten years ago, I would have ended up doing public health work in some shape, form or fashion. I have always been convinced of the power of preventive care over curative care, comprehensive primary health approaches over tertiary centers of excellence, and the need to address population health needs to ameliorate the health conundrums facing the nation.

And then there were the pandemic years…

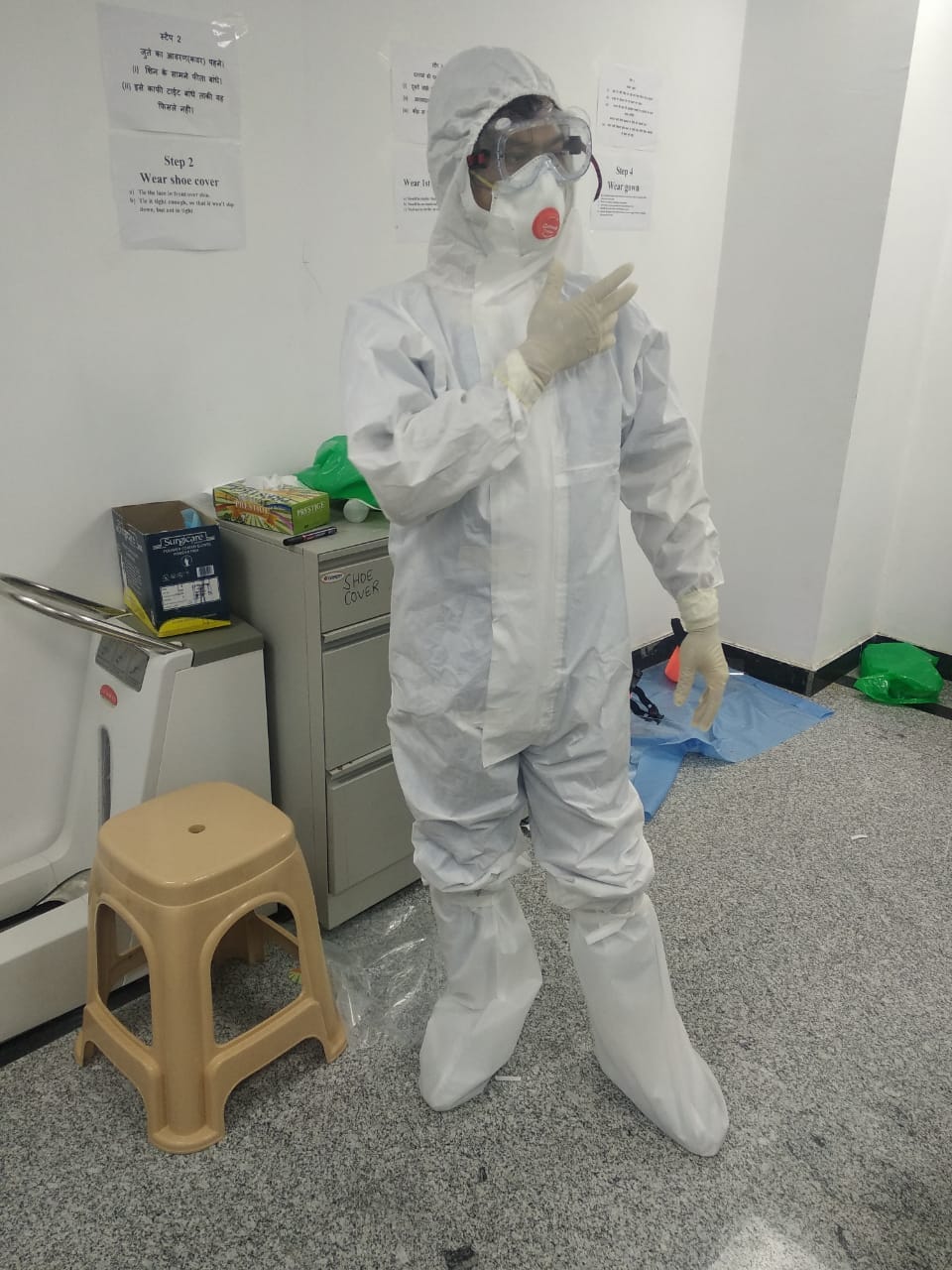

By early 2020, I was in New Delhi, working at the headquarters of the Indian Council of Medical Research when COVID-19 broke out. I found myself drafted to manage the Secretariat of the National Task Force on COVID-19, the apex policymaking body directing India’s pandemic response. I was responsible for rapid evidence synthesis to support real-time decision-making. In those frantic early months, as the world was grappling with an entirely novel pathogen, I published a rapid review of COVID-19 epidemiology and public health response that was cited hundreds of times and helped shape India’s initial policy response. But it was during the second wave of the pandemic, when India’s health systems were crippled by a shortage of oxygen, that I learned the most humbling lesson: policy papers and evidence syntheses mean nothing if you’re not on the ground, delivering oxygen concentrators to communities that are suffocating for lack of it. That experience fundamentally shifted something in my thinking about what public health work actually means.

On a lighter note, this experience was also how my dear friend Anup and I came up with a new framework of estimating the effectiveness of public health interventions. We compared proposed public health interventions and asked if it was more or less effective than standing in front of ICMR and distributing hand sanitizers. Ashwagandha for COVID immunity? Ivermectin? Fancy drugs that cost a bomb for severe COVID-19? Our framework stoof the test of time!

It was against this backdrop that I decided to move to the US to pursue my PhD at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. My doctoral research is centered on understanding the preferences and behaviors of both formal and informal prescribers, and the patients and caregivers who seek out antibiotics, in rural India. I’m investigating the question that has animated much of my research over the years: what drives antibiotic overuse at the community level, and how can we address it without simply imposing top-down restrictions that ignore local realities? This work has taken me back to the villages and towns of India repeatedly, sitting with pharmacists, clinicians, and families, trying to understand how they navigate a healthcare landscape that is fractured, inequitable, and often fails them.

Over the past three years, my research focus has also sharpened around questions of power, knowledge, and epistemic justice in how we construct and disseminate global health knowledge itself. I contributed to work on using anti-oppressive teaching principles in graduate global health courses at Johns Hopkins, grappling with how a field born out of colonialism and tropical medicine continues to perpetuate colonial structures and ways of knowing. I was involved in developing pedagogical approaches that interrogate these very foundations. I’ve also been thinking deeply about what decolonization of global health actually means; not merely as a diversity and inclusion effort, but as a fundamental dismantling of the feudal structures that continue to concentrate knowledge, funding, and agenda-setting power in the institutions of the Global North.

To be clear, though, I am skeptical of how DEI has often been deployed, particularly in American academia and institutions. DEI in practice has frequently become a box-ticking exercise; a veneer of diversity that papers over the persistence of structural inequalities while providing moral cover to institutions that remain fundamentally unchanged. Adding a few faces from the Global South to grant committees, hiring a diversity officer, or mandating unconsciousness training does nothing to dismantle the feudal architecture of global health itself. In fact, it can paradoxically entrench it further by lending legitimacy to institutions that continue to hoard resources, control agendas, and position themselves as the arbiters of knowledge. True decolonization isn’t about making oppressive systems slightly more inclusive; it’s about recognizing and fundamentally challenging the power imbalances that allow those systems to persist in the first place. It requires the kind of honest reckoning with structural injustice that makes many institutions uncomfortable; and that is precisely why it remains so rare in practice. Anyway. That is a post for another day.

One thing that I look back and identify, almost always, is the serious lack of role models most MD graduates in Preventive and Social Medicine experience. I was in a uniquely empowered position, and went to training programs with incredible individuals, both in the personal and professional spaces. When I look around, however, I see most PSM MD graduates are far from being that fortunate. This drove me to start writing the Careers in PSM series on this blog, and eventually, led me to consider the idea of consolidating these experiences and anecdotes about public health careers to enable and empower the next generation of public health students.

With that in mind, I decided to work with a friend to launch a website dedicated to providing not just MD students, but a broader swathe of students, both from medical and non-medical backgrounds, with real life evidence and role models to emulate and build their public health careers. This work has evolved; the Global Public Health eXchange (GPHX) now exists as both a website and a podcast platform where students and practitioners of public health come together to exchange ideas and expertise, learn from one another, and co-create a community of practice. It remains a nascent endeavor, but one I believe is more necessary than ever as we grapple with how to reimagine public health education itself and make it truly decolonial.

The last decade and a half have seen me take a long and tortuous road in my career pathway. From being a somewhat lost MD student wondering if I’d made a terrible mistake, through my work as a scientist at the Indian Council of Medical Research, my engagement with policymaking at the highest levels of government during the COVID-19 pandemic, to becoming, well, a somewhat less lost PhD student at Johns Hopkins, trying to hold together the tension between rigorous epidemiology and the lived realities of the communities I study. Somehow thirteen years have slipped by. And you know what, despite everything I feel on the rare “off day,” I would not have it any other way. The record shows, I took the blows and did it my way.