From Risk to Resource: Professionalizing Informal Veterinary Healthcare Providers for Strengthening our One Health Future

Talking about the controversial move to integrate informal veterinary healthcare providers into the formal systems and why that is the disruptive change we need to combat the global threat of AMR.

Introduction: The Animal Friend's Dilemma

The sun beats down on the cracked earth. Summers in Purulia can be unforgiving. Eddies of dust swirl in the warm air as the afternoon heat wave ripples through this bucolic corner of rural West Bengal. Inside a small, mud-walled hut, a family watches their most valuable possession – a dairy cow – struggle to breathe. Her fever is high, her milk has dried up, she hasn't eaten in over four days. What began as a small limp that the family ignored for a few days has rapidly cascaded into a potential catastrophe. For this family, she is not just an animal; she is their bank account, their children's source of nutrition, their entire net worth walking on four legs. Perhaps I am being disrespectful referring to the beloved animal in such material terms, because for most of the households in this village, their livestock and poultry are like extensions of their natural, human families. It is truly an interdependent way of life where humans and animals live together through precarious climate – both economic and meteorological.

The nearest government veterinarian is a full day's journey away, an impossible distance over rutted roads. There is no guarantee having hauled the sick animal all the way to the town clinic, that they would be able to access the healthcare services she needs. Most services in government clinics are either free or come for a nominal fee – the crippling expense comes in when the animal needs to be transported over undulating terrains and potholed roads. It is not an easy affair to haul a thousand-pound animal over miles of unforgiving roads.

A single phone call brings a different kind of help. He arrives on a sputtering motorbike, a worn bag slung over his shoulder. He is not a veterinarian, not officially anyway. In this part of India, he is known as the Private Doctor, a friend to the family when they really need one. In other parts of the world, he might be called a para-vet or a Community Animal Health Worker (CAHW) (Sudhinaraset et al., 2013). He is a neighbor, a familiar face. He listens patiently, nods with an air of confidence, and rummages through his bag. He pulls out a syringe and a small, unlabeled bottle of liquid. A quick injection, a few words of assurance, and a small fee is exchanged. For now, hope is restored. The private doctor leaves the family a couple of pills, several words of reassurance and asks them to give him a call and update him after 24 hours.

He swings onto his trusted steed and pumps the kick-starter – once, twice, and a third time, before the geriatric motorbike sputters to life, belching thick black smoke; phone pressed to his ear, he rattles off toward his next call of care.

This scene, or one very much like it, plays out millions of times every day across the globe. In the vast landscapes of Asia, Africa, and Latin America, where over 1.5 billion people rely on livestock to survive, these informal providers are the beating heart of animal healthcare (World Organisation for Animal Health, 2019). They are the indispensable frontline responders in a system riddled with what experts call “Manpower and Service Delivery Gaps” (Bugeza et al., 2017). They step into the void left by formal veterinary services, offering a lifeline to the world's most vulnerable farmers. They are accessible, affordable, and, most importantly, trusted (Sudhinaraset et al., 2013). But herein lies a dangerous paradox, a dilemma hidden within the dusty contents of the animal friend’s bag. His "magic potions" are often a cocktail of antibiotics, steroids and other modern medicines, acquired from unregulated street-side stalls, with little knowledge of the right drug, the right dose, or the right disease (College of Veterinary Medicine & The Ohio State University, 2025). His well-intentioned actions, repeated millions of times over, are inadvertently fueling a silent, creeping pandemic: antimicrobial resistance (AMR) (Liu et al., 2023). He is, at once, a local savior and a global threat.

This is the story of that paradox.

It is an argument that we cannot simply ignore the informal providers or just wish him away. He is too essential. Instead, we must embark on a journey of transformation. By recognizing, training, and welcoming these informal providers into the official family of animal healthcare, we can turn them from unintentional vectors of risk into our most powerful allies in the fight for a healthier planet. This is not just a story about vets and cows. It's a story about safeguarding our food, our economies, and our own health from the interconnected threats of disease and drug resistance, a concept known as One Health (University of Minnesota, 2023; World Health Organization, 2021). The animal friend stands at a crossroads. By helping him choose the right path, we can help secure a safer future for us all.

1. The Double-Edged Sword: The World of the Para-Vet

To understand the para-vet's dilemma, we must first walk a mile in his shoes. We must see the world as he sees it: a world of desperate need, of deep community bonds, and of dangerous, hidden, fallacious costs. His existence is not an accident; it is a direct consequence of a system that has failed the very people it is meant to serve… and that he has managed to monetize and leverage to help himself and the community he shares space with.

1.1. The Great Veterinary Desert

Imagine a map of the world’s animal health services. In the cities and wealthy farming belts, you would see bright clusters of light, the clinics of highly trained, well-equipped veterinarians (Rondeau, 2023). But as you move out into the remote rural and pastoral lands, those lights flicker and die out, leaving a vast and dark “veterinary desert”. This is the world where the majority of the planet's smallholder farmers live, and it is a desert of our own making.

Beginning in the 1980s, a wave of economic reforms saw many governments cut back on public services, including veterinary care, hoping the private sector would fill the gap (Rondeau, 2023). It was a gamble that didn't pay off. Private vets, needing to make a living, naturally set up shop where the money was: serving large commercial farms or wealthy pet owners in the cities. The economics of serving a poor farmer with two goats and a cow in a village a hundred miles from the nearest paved road simply didn't add up (Bugeza et al., 2017). The state vanished, but the private market never arrived. Into this vacuum stepped the informal provider. He was a local resident, willing to travel by foot or motorbike, ready to accept a small payment or even barter for his services. He became the only option. Studies show that in some regions, these para-vets handle up to 90% of all animal health needs (Sudhinaraset et al., 2013). They are not a fringe element; they are the system.

This reality challenges how conventional health systems approach teaches us to think about the problem. Any plan to simply ban these providers is not only destined to fail, but it would also be cruel. It would be like bulldozing a settlement’s only well without providing a new source of water. You wouldn't eliminate the problem; you would only deepen the crisis. The goal cannot be eradication. It must be transformation.

1.2. The Currency of Trust

If the veterinary desert explains why para-vets exist, the secret to their success, the reason a farmer calls them instead of waiting for a government official, can be summed up in one word: trust.

Formal systems, with their bureaucratic forms, unfamiliar jargon, and nine-to-five city office hours, often inspire more suspicion than confidence (Bugeza et al., 2017). Trust, researchers have found, isn't just about a fancy degree. It's built on empathy, on feeling heard, on a provider who shows genuine concern and speaks your language (PetDesk, 2025). This is the para-vet and informal providers’ home turf. He is a member of the community (Scholz & Trede, 2023). He understands the subtle cultural cues, knows the family’s history, and is available at midnight when a cow is having a difficult birth (Maiti et al., 2011). He doesn't just treat the animal; he reassures the owner. This deep, relational bond is a ‘trust dividend’ that formal systems struggle to earn. An evaluation of the Prani Bandhu program in West Bengal found that while farmers knew these men weren't official vets, they valued them immensely for one simple reason: they always showed up (Maiti et al., 2011).

This insight is a game-changer. It tells us that any attempt to “professionalize” these providers that focuses only on textbooks and technical skills is doomed. We would be creating a cadre of junior vets who are technically better but have lost the very “superpower” – their community connection – that made them effective without their technical training. The World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) wisely recognizes this, including a whole section on “Engaging with the Community” in its training guidelines for these workers (World Organisation for Animal Health, 2024). To succeed, we must build on their trust, not replace it.

1.3. The Invisible Plague in the Bag

Now we must look inside the para-vet’s worn leather bag, for it contains both the cure and the curse. The same accessibility that makes him a hero also makes him a major source of a global health nightmare.

Imagine every antibiotic is a unique key, designed to unlock and disable a specific type of bacteria. Now imagine that every time we use a key incorrectly, using the wrong one for the wrong lock, or only turning it halfway, the lock “learns”. It changes its internal tumblers, ever so slightly. Soon, the key no longer works. This is antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in a nutshell. And the para-vet, with his bag of assorted, often mysterious “keys”, is unintentionally teaching the world’s deadliest germs how to change their locks.

This happens in three ways. First, without proper training or diagnostic tools, his choice of drug is often a blind guess (College of Veterinary Medicine & The Ohio State University, 2025). He might use a powerful, broad-spectrum antibiotic for a simple viral infection where it has no effect, like using a master key on a door that's already open. Second, he gets his drugs from a chaotic, unregulated market of back-alley shops and itinerant salesmen (Jaime et al., 2022). These drugs can include antibiotics that are deemed “critically important” for saving human lives, and they are sold to him without a prescription like candy (Dione et al., 2021). Third, and perhaps most terrifyingly, these drugs are often fake. They may be expired, stored in the blistering sun, or deliberately counterfeited with chalk dust instead of active ingredients (Lemma et al., 2025). When a sick animal gets a dose of this junk medicine, it’s like turning that antibiotic key only halfway. The weakest bacteria are killed, but the strongest survive. These “superbugs” then multiply, now armed with a genetic memory of how to defeat our best medicines (Hufnagel, 2020).

This isn’t just a problem for cows and goats. Animal agriculture is a massive factory for creating resistant germs (Liu et al., 2023). These superbugs travel from the farm to our families. They contaminate meat, milk, and eggs. They seep into the soil and water from animal manure. They pass directly to farmers through simple contact. Suddenly, a resistance gene that was born in a chicken shed in a remote village can end up in a hospital in a major city, rendering our last-resort antibiotics useless against a child’s bloodstream infection. This isn’t a hypothetical threat anymore. AMR is already killing over a million people a year, a silent pandemic that threatens to send modern medicine back to the dark ages (Ballash et al., 2024; Naghavi et al., 2024). The para-vet, the animal friend on his motorbike, stands at the very epicenter of this crisis. He is the gatekeeper. The final decision to use an antibiotic on the farm is his. To win the war against superbugs, we don’t just need new laws in capital cities; we need to win the hearts and minds of the men and women on the front lines. We need to transform them from gatekeepers into guardians.

2. A Framework for Transformation: Forging a New Kind of Hero

How do we turn a well-meaning but dangerous amateur into a trained, accountable professional? It can’t be done with workshops or pamphlets. It requires a complete overhaul, a hero’s journey of transformation built on three powerful pillars: giving them a badge, equipping them the right decision-making heuristics, and inviting them to join the league of heroes.

2.1. Pillar 1: A Badge and a Rulebook – Formal Recognition

The first step is to bring the para-vet out of the shadows. For too long, they have operated in a legal grey zone, officially ignored, unofficially tolerated (Rondeau, 2023). This has to end. They need a badge, a formal, legal status that recognizes their existence and their importance. This means rewriting the old laws, the Veterinary Council of India’s standards and acts, to create an official space for them.

Countries in West Africa have already started drawing these lines, creating legal roles for para-professionals (Luseba, 2015). The American Veterinary Medical Association provides a model “rulebook” that can be adapted, helping to standardize titles and responsibilities (American Veterinary Medical Association, 2025). This legal recognition is the foundation for everything else. It creates clear lines of authority, establishes accountability, and gives the informal para-vet a sense of professional pride and purpose (Bugeza et al., 2017). But a badge alone is not enough. The cautionary tale of Cambodia shows us why. The country gave official status to thousands of Village Animal Health Workers (VAHWs), but years later, nearly half of them were inactive (Veterinaires Sans Frontieres, 2024). A badge is just a license to operate; it doesn’t pay the bills or keep your skills sharp. India’s Prani Bandhu program faces similar struggles, with endless debates about what they should and shouldn't be allowed to do, even with government backing (Barbaruah, 2016). The law must be the start of the journey, not the end. It must be backed up by real enforcement and a system that allows these newly minted officers to actually succeed (Willems, 2007).

2.2. Pillar 2: The Core Competencies of Modern Medicine

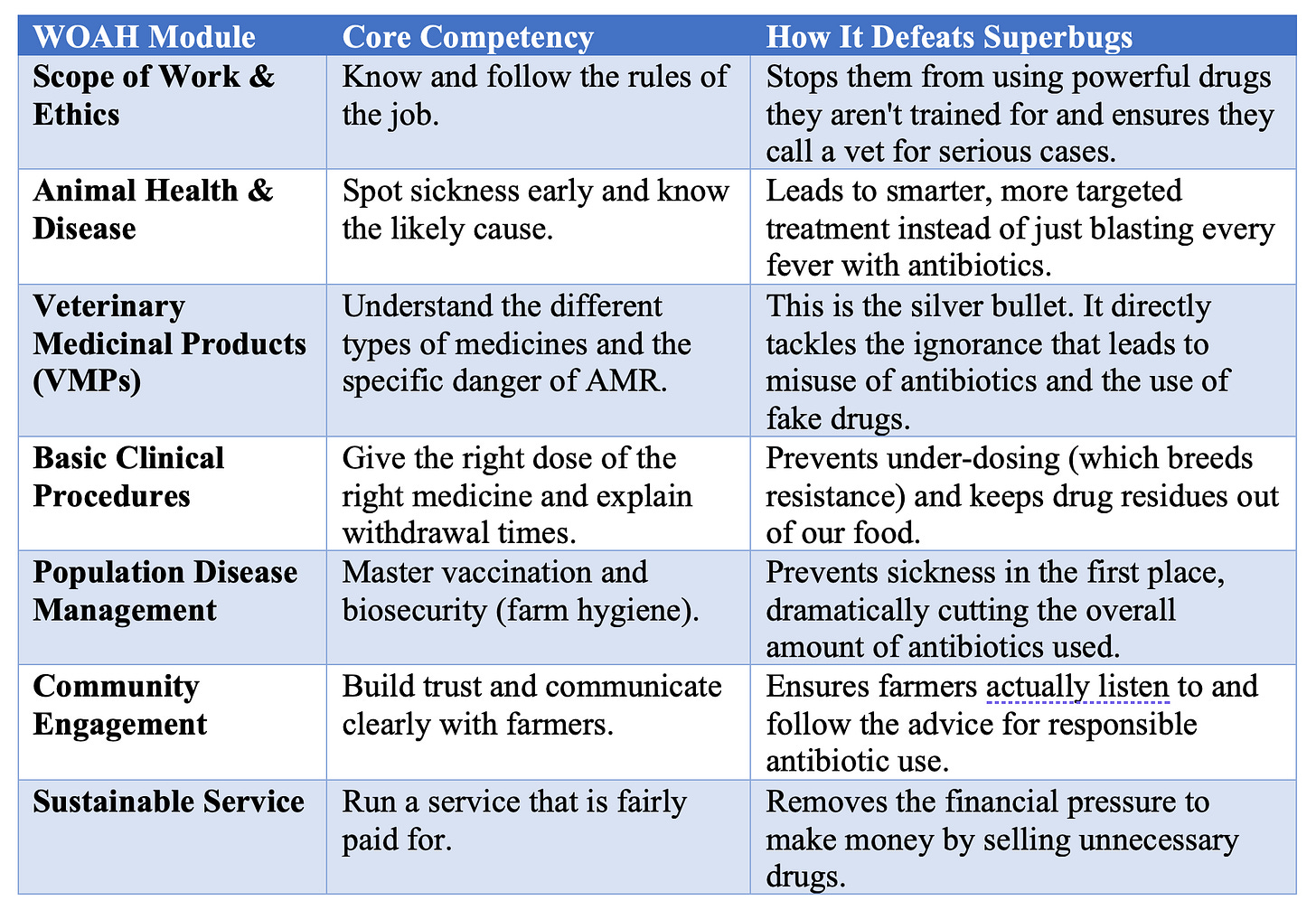

For decades, training for para-vets has been a chaotic mess of short, informal workshops run by different aid groups, each with its own ideas of what is important, and what is not (Rondeau, 2023). The result is a workforce with wildly inconsistent skills and dangerous gaps in knowledge. It’s time to throw out the scattered notes and give everyone the same, official spellbook. Fortunately, that spellbook has already been written. The World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) has created a global gold standard: the Competency and Curriculum Guidelines for Community Animal Health Workers (World Organisation for Animal Health, 2024). This isn’t just another training manual. It's a harmonized, internationally approved blueprint that countries can use to build a truly professional class of providers. The WOAH guidelines are a masterclass in what a modern para-vet needs to know. They go far beyond just jabbing needles into animals. They teach:

· The Rules of the Game (Module 1): Understanding their legal role, their code of ethics, and, crucially, knowing their limits.

· Reading the Signs (Modules 2 & 5): The fundamental skill of telling a healthy animal from a sick one and recognizing the tell-tale signs of common diseases.

· Mastering the Skills (Module 7): This is the heart of antimicrobial stewardship. It’s where they learn about the different kinds of medicines, why using quality drugs matters, and the terrible risks of AMR. It’s where they learn not to use a sledgehammer to crack a nut.

· The Power of Prevention (Module 8): Shifting the mindset from constantly fighting fires (treating sick animals) to building fireproof houses (preventing disease through vaccination and clean practices).

· The Art of Persuasion (Module 10): Honing the “soft skills” of communication that allow them to build trust and convince a skeptical farmer to follow their advice.

· Making a Living (Module 11): The practical business skills needed to run a sustainable service, ensuring they can support their own families while serving the community.

This is how you fight AMR at its source. You don't just tell them “AMR is bad.” You teach them how to be better diagnosticians, so they don't need to guess with a broad-spectrum antibiotic. You teach them about the dangers of counterfeit drugs. You give them the communication skills to explain to a farmer why they must wait a week before drinking milk from a treated cow. This is strategic, targeted, and transformative.

Table 1: The Para-Vet's New Toolkit for Fighting Superbugs (Adapted from WOAH CAHW Guidelines)

2.3. Pillar 3: Joining the League of Heroes – Systemic Integration

A trained para-vet with a badge is a powerful asset. But a trained para-vet who is a formal part of a national team is a superhero. The final pillar of transformation is integration: welcoming these providers into the official animal health system, not leaving them to fend for themselves. This means creating a clear chain of command. Every para-vet should have a mentor, a registered veterinarian or a senior professional they can call for advice, who checks their work, and who holds them accountable. This mentorship is a lifeline, providing technical backup and continuous on-the-job learning. It also means building a functional referral system. When a para-vet faces a problem too big for them to handle, there must be a clear, simple, and affordable way to pass the case up the chain to a full veterinarian. This ensures the animal gets the best possible care and builds public confidence in the entire system.

Most excitingly, integration turns the para-vet into a public health sentinel. With their ears to the ground in thousands of remote villages, they are the perfect early warning system for disease outbreaks. Imagine a network of 10,000 trained para-vets all reporting into a central system. They could spot the first signs of a new zoonotic flu, a potential foot-and-mouth disease outbreak, or a new anthropozoonotic threat before it explodes into a regional crisis. In West Africa, trained CAHWs are already doing this, reporting thousands of disease events and helping to control devastating plagues like Peste des Petits Ruminants (PPR) (Sow et al., 2023).

How can a country map this out? WOAH provides another powerful tool: the Performance of Veterinary Services (PVS) Pathway (World Organisation for Animal Health, 2025a). It's like a comprehensive physical for a country’s entire animal health system. It helps leaders identify their weaknesses, particularly in their workforce, and create a strategic plan to integrate para-vets effectively (World Organisation for Animal Health, 2025b). It provides the blueprint for building a modern, multi-tiered animal health army. Finally, integration must be digital. In the 21st century, every recognized provider, from the top vet to the village para-vet, should be in a national database. This allows officials to instantly verify credentials, track drug distribution, and manage outbreak responses with speed and precision. By bringing the para-vet into the system, they cease to be just a guy on a motorbike; they become a vital node in a national network of health and security.

3. Tales from the Field: Stories of Triumph and Trouble

The three-pillar framework of recognition, education, and integration sounds great in theory. But the real world is messy. The stories of para-vet programs from around the globe are not simple fables of success or failure. They are complex tales of good intentions, unexpected obstacles, and hard-won lessons that can guide us forward.

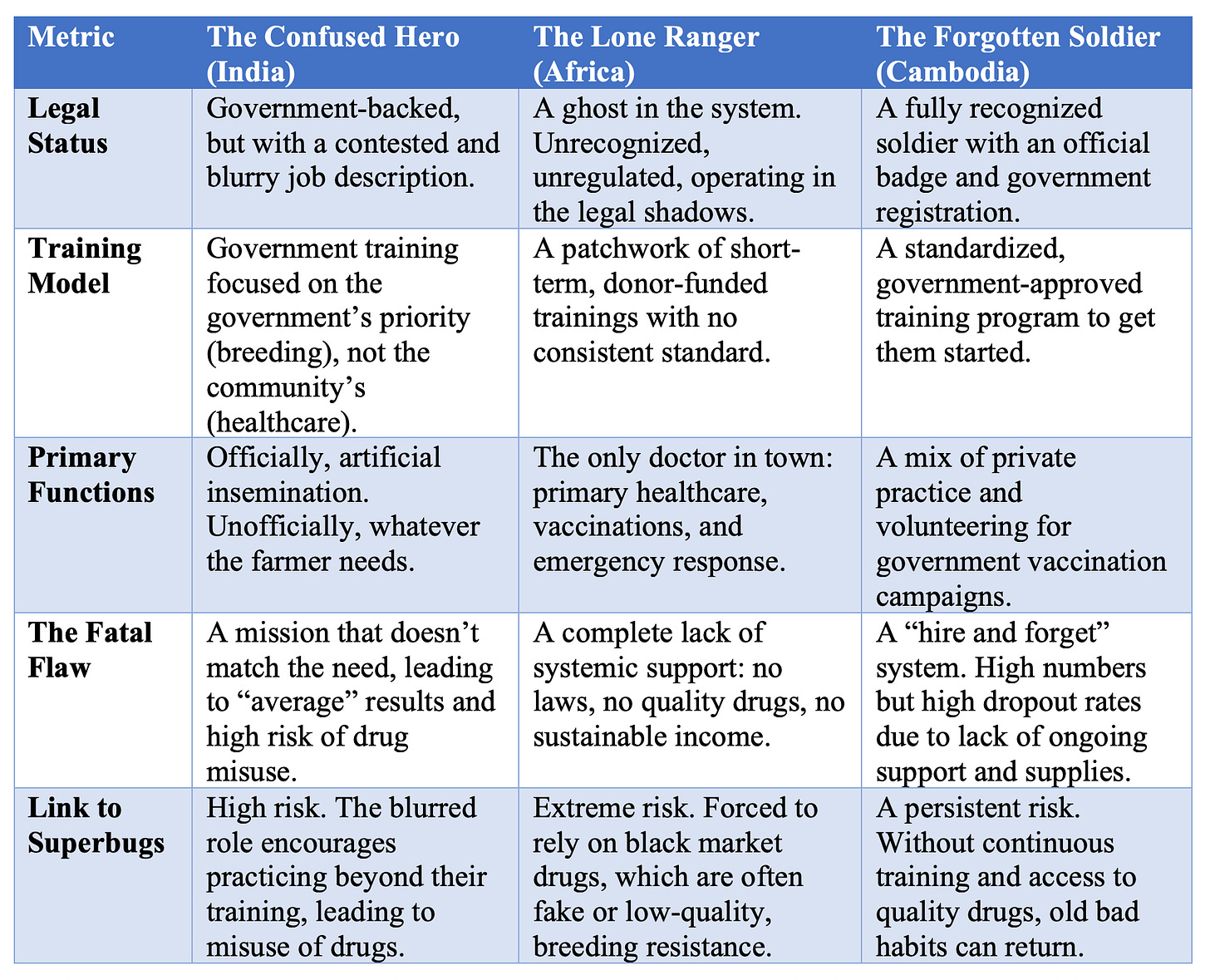

3.1. The Case of the Confused Mission: India's “Prani Bandhu”

In the Indian state of West Bengal, the government launched an ambitious program called Prani Bandhu (literally “Friends of Animals”). The idea was to train unemployed young people to provide doorstep services to farmers, creating jobs and improving livestock productivity through a Public-Private Partnership (Maiti et al., 2011).

On the surface, it seems to be working well. The Prani Bandhus were deployed, and farmers were happy to have someone, anyone, they could call in an emergency. But dig a little deeper, and the story gets complicated. The government's top priority was breeding. They trained the

Prani Bandhus primarily to perform artificial insemination (AI) to create more productive crossbred cows. But what did the farmers really want? They wanted someone to treat their sick animals. This created a fundamental conflict. The providers were measured on their AI targets, but their customers wanted them to be doctors. The result? Everyone was just “somewhat satisfied.” Performance was rated as “average” across the board. Worse, because their role was so blurry, it opened the door to risk. They were performing a technical task (AI) but were also being pressured to act as vets, often using drugs without proper training or supervision, raising all the alarms about fueling AMR.

The moral of the Prani Bandhu story is that you can’t push a solution, no matter how well-intentioned, from the top down. The mission must be aligned with the community's actual needs. Otherwise, you end up with a confused hero, trying to do one job while the world is screaming at him to do another.

3.2. Lone Rangers of the Savannah: Africa’s CAHWs

Across the vast, arid landscapes of Sub-Saharan Africa, a different story unfolds. Here, the heroes are the Community Animal Health Workers (CAHWs), often trained by international aid groups to serve the most remote and conflict-affected pastoralist communities. And they are true heroes. Study after study from Kenya, Uganda, Ethiopia, and even war-torn South Sudan shows that CAHWs are deeply valued and incredibly effective (Leyland et al., 2014). They save livestock, which are the lifeblood of these communities, and in doing so, they protect families from starvation (Okoth, 2024). In many of these places, they are the only sliver of hope in the veterinary desert.

But these heroes are fighting with one hand tied behind their backs. They are lone rangers, operating without official support. Most have no legal status, no badge to prove their legitimacy. They struggle to find quality medicines, often forced to buy from the same shady dealers they are trying to replace (Jaime et al., 2022). And their work is precarious, often dependent on the whims of donor funding. When a project ends, their support system, their supply of fresh medicine kits, their small stipend vanish overnight, leaving them and their communities stranded once again (Leyland et al., 2014).

The lesson from Africa is powerful: a hero is only as good as his sidekick. You can train the most skilled provider in the world, but if you send him into the wilderness without the shield of technical expertise, with no access to effective essential diagnostics and medicines, lacking a reliable supply line, or a way to make a sustainable living, he will eventually fail. The focus must shift from simply training heroes to building a system that supports them.

3.3. The Forgotten Army: Cambodia's VAHWs

Cambodia’s story offers the final, crucial piece of the puzzle. Here, the government did almost everything right, at least on paper. They created a formal system of Village Animal Health Workers (VAHWs), gave them legal recognition, and scaled up the program to cover nearly every village in the country: a registered army of over 11,000 providers (Veterinaires Sans Frontieres, 2024). It was a model of official commitment.

But a few years ago, a shocking report emerged: only 47% of this great army was still active. The rest had simply faded away. Why? The government had issued the badges and provided the initial training, but then the support stopped. The VAHWs complained that their skills were getting rusty without regular refresher courses. They couldn't compete with the informal drug sellers because they had no reliable access to affordable, high-quality medicines. They felt forgotten and unappreciated. The Cambodian case is perhaps the most sobering lesson of all. It proves that even legal recognition and massive scale are not enough. Professionalization is not a one-time event; it is a continuous process. An army, no matter how large, is useless if it runs out of ammunition and its commanders forget it exists. The solution, some have found, is for the VAHWs to band together, forming cooperatives to buy supplies in bulk and advocate for themselves. They are learning that if the system won't support them, they must support each other.

Table 2: A Tale of Three Heroes: Comparing Para-Vet Models

4. The Path Forward: Choosing Our Champions

The story of the informal veterinary provider is the story of a problem that is also a solution. We stand at a global crossroads. Down one path lies the status quo: a world where millions of well-meaning but undertrained individuals continue to be a primary engine of antimicrobial resistance, the silent pandemic that threatens us all. Down the other path lies transformation: a world where we invest in these individuals, train them, support them, and turn them into an army of antimicrobial stewards.

The choice creates two very different futures. The first is a vicious cycle. Gaps in formal veterinary care lead to more unregulated providers. Their limited training and reliance on black-market drugs drive the misuse of antibiotics. This breeds superbugs that undermine both animal and human health, creating even more sickness and straining our fragile health systems.

The second path creates a virtuous cycle. We give the para-vet a badge (legal recognition). We give him a proper spellbook (standardized training). We invite him to join the league of heroes (systemic integration). In this future, a newly professionalized provider improves animal health through prevention and smart treatment. This reduces the overall need for antibiotics. He becomes a trusted guardian of his community’s health and a vital sentinel protecting the rest of the world from the next disease outbreak.

This is not a fringe issue. This is a cornerstone of global health security. As the nations of the world declare war on AMR, the professionalization of the para-vet must be written into every country’s battle plan (Thomas, 2025). They are our ground troops, the ones who can turn policy into practice on the farm. Investing in them is a direct investment in the One Health ideal: the simple, powerful idea that the health of people, animals, and the environment are all woven together.

The time for pilot projects and academic debates is over. The path forward requires bold, concerted action.

A Call to Action for Governments and Veterinary Leaders:

1. Rewrite the Rulebook: Update your national veterinary laws. Create a formal, legal home for the para-veterinary professional. Use the world's best practices from WOAH and others to define what they can and cannot do, creating a clear, tiered system of care.

2. Adopt the Gold Standard: Make the WOAH CAHW Competency Guidelines the official national standard for training and accreditation. End the chaos of inconsistent, ad-hoc training. Ensure every provider learns from the same high-quality spellbook.

3. Build One Team: Use strategic tools like the WOAH PVS Pathway to formally integrate these professionals into your national system. Give them a role in disease surveillance, a seat at the table, and a connection to the national data network. Turn your scattered freelancers into a cohesive public health army.

A Call to Action for Donors and Aid Organizations:

1. Build Systems, Not Projects: Stop funding short-term training workshops that evaporate when you leave. Invest in the long-term enabling environment. Fund the advocacy needed to change laws. Help build legitimate, quality-controlled supply chains for veterinary medicines. Teach business skills, not just technical skills.

2. Demand Quality: Make your funding conditional on quality. Insist that any training program you support aligns with the international WOAH guidelines. Use your financial leverage to raise the bar for everyone.

3. Invest in Success: Focus on creating sustainable careers. Help providers form cooperatives, access micro-finance, and build viable businesses that don't rely on your subsidies to survive.

In the end, the story comes back to the farmer, his sick cow, and the man on the motorbike. The choice we face is what happens next. Do we leave them to fumble in the dark, using failing keys on ever-changing locks? Or do we give that man a new set of keys, a map, and a radio to call for backup when he needs extra help? Do we turn a well-meaning gambler into a trained first responder? By investing in the transformation of these millions of “animal friends,” we do more than just save livestock. We strengthen food security, build economic resilience, and forge a vital frontline defense in the global war against superbugs. This is not a cost. It is one of the smartest investments we can make in our shared, one-health future.

References:

American Veterinary Medical Association. (2025). Model Veterinary Practice Act. AVMA. https://www.avma.org/resources-tools/avma-policies/model-veterinary-practice-act

Ballash, G. A., Parker, E. M., Mollenkopf, D. F., & Wittum, T. E. (2024). The One Health dissemination of antimicrobial resistance occurs in both natural and clinical environments. Journal of American Veterinary Medical Association, 262(4), 451–458. https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.24.01.0056

Barbaruah, M. I. (2016). Skilling veterinary para-professionals for sustainable livestock sector development: An account of the ongoing policy advocacy in India. Proceedings of UGC-SAP National Seminar, 37–43. https://www.vethelplineindia.co.in/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/DetailTalk_UGC-SAPNationalSeminar_SkillingIndia.pdf

Bugeza, J., Kankya, C., Muleme, J., Akandinda, A., Sserugga, J., Nantima, N., Okori, E., & Odoch, T. (2017). Participatory evaluation of delivery of animal health care services by community animal health workers in Karamoja region of Uganda. PLOS ONE, 12(6), e0179110. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0179110

College of Veterinary Medicine, & The Ohio State University. (2025, March 17). Helping Community Animal Health Workers enhance skills with dedicated training guidelines | College of Veterinary Medicine. https://vet.osu.edu/news/helping-community-animal-health-workers-enhance-skills-dedicated-training-guidelines

Dione, M. M., Amia, W. C., Ejobi, F., Ouma, E. A., & Wieland, B. (2021). Supply Chain and Delivery of Antimicrobial Drugs in Smallholder Livestock Production Systems in Uganda. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2021.611076

Hufnagel, H. (2020). The Quality of Veterinary Pharmaceuticals: A Discussion Paper for the Livestock Emergency Guidelines and Standards (LEGS) (p. 19). Livestock Emergency Guidelines And Standards. https://doi.org/10.3362/9781780440262

Jaime, G., Hobeika, A., & Figuié, M. (2022). Access to Veterinary Drugs in Sub-Saharan Africa: Roadblocks and Current Solutions. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2021.558973

Lemma, M., Alemu, B., Amenu, K., Wieland, B., & Knight-Jones, T. (2025). Enhancing community awareness of antimicrobial use and resistance through community conversations in rural Ethiopia. One Health Outlook, 7(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42522-025-00148-6

Leyland, Ti., Lotira, R., Abebe, D., Bekele, G., & Catley, A. (2014). Community-Based Animal Health Workers in the Horn of Africa: An Evaluation for the Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (p. 84). Feinstein International Center, Tufts University Africa Regional Office, Addis Ababa and Vetwork UK, Great Holland. https://fic.tufts.edu/wp-content/uploads/TUFTS_1423_animal_health_workers_V3online.pdf

Liu, B., Wang, W., Deng, Z., Ma, C., Wang, N., Fu, C., Lambert, H., & Yan, F. (2023). Antibiotic governance and use on commercial and smallholder farms in eastern China. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2023.1128707

Luseba, D. (2015). Review of the policy, regulatory and administrative framework for delivery of livestock health products and services in West and Central Africa (p. 41). GALVMed. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5aa66772e5274a3e3603a626/47_West_Africa_Review_of_Policy__Regulatory_and_Administrative_Framework_for_Delivery_of_Livestock_Health_Products.pdf

Maiti, S., Jha, S. K., & Garai, S. (2011). Performance of Public-Private-Partnership Model of Veterinary Services in West Bengal. Indian Res. J. Ext. Edu., 11(2), 1–5.

Naghavi, M., Vollset, S. E., Ikuta, K. S., Swetschinski, L. R., Gray, A. P., Wool, E. E., Aguilar, G. R., Mestrovic, T., Smith, G., Han, C., Hsu, R. L., Chalek, J., Araki, D. T., Chung, E., Raggi, C., Hayoon, A. G., Weaver, N. D., Lindstedt, P. A., Smith, A. E., … Murray, C. J. L. (2024). Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance 1990–2021: A systematic analysis with forecasts to 2050. The Lancet, 404(10459), 1199–1226. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01867-1

Okoth, S. (2024). Community Animal Health Workers (CAHWs) in South Sudan: Strengths, Weaknesses and Prospects (Strengthening the Enabling Environment for Community Animal HealthWorkers (CAHWs) through Development of Competency and Curricula Guidelines, p. 49). World Organization of Animal Health. https://fscluster.org/sites/default/files/documents/CAHW%20Case%20Study%20Report%20South%20Sudan.pdf

PetDesk. (2025, February 24). Building Trust Through Transparent Veterinary Communication. PetDesk. https://petdesk.com/blog/communication-strategies-veterinary-practices/

Rondeau, A. (2023, July 31). Community animal health workers or CAHWs and the provision of basic animal health services. World Veterinary Association. https://worldvet.org/news/community-animal-health-workers-or-cahws-and-the-provision-of-basic-animal-health-services/, https://worldvet.org/news/community-animal-health-workers-or-cahws-and-the-provision-of-basic-animal-health-services/

Scholz, E., & Trede, F. (2023). Veterinary professional identity: Conceptual analysis and location in a practice theory framework. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2023.1041475

Sow, A., Kane, Y., Boka, M., Kohagne, K.-T. L., Bitek, A., Nantima, N., Ouagal, M., Ndiaye, R., Ahmed, I., Bobo, G., Seck, I., Wolde, A., & Soumare, B. (2023). Community Animal Health Workers (CAHWs) contribution in detection and response to priority transboundary animal diseases and zoonoses in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. Research Square. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3334676/v1

Sudhinaraset, M., Ingram, M., Lofthouse, H. K., & Montagu, D. (2013). What is the role of informal healthcare providers in developing countries? A systematic review. PloS One, 8(2), e54978. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0054978

Thomas, J. (2025, May 30). Global drop in antimicrobial use in animals finds WOAH report, but more action needed. Innovation News Network. https://www.innovationnewsnetwork.com/global-drop-in-antimicrobial-use-in-animals-finds-woah-report-but-more-action-needed/58575/

University of Minnesota. (2023, May 31). Antimicrobial Resistance Learning Site: One Health. https://amrls.umn.edu/one-health

Veterinaires Sans Frontieres. (2024, April 12). Case Study on Village Animal Health Workers (VAHWs) in Cambodia: Recommendations for Addressing Future Challenges. VSF International. https://vsf-international.org/case-study-vahws-cambodia/

Willems, R. A. (2007). Animals in Veterinary Medical Teaching: Compliance and Regulatory Issues, the US Perspective. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 34(5), 615–619. https://doi.org/10.3138/jvme.34.5.615

World Health Organization. (2021). Tripartite and UNEP support OHHLEP’s definition of “One Health.” WHO News. https://www.who.int/news/item/01-12-2021-tripartite-and-unep-support-ohhlep-s-definition-of-one-health

World Organisation for Animal Health. (2019). Strengthening Veterinary Services Through the OIE PVS Pathway: The Case for Engagement and Investment (p. 39). World Organization of Animal Health. https://www.woah.org/app/uploads/2021/03/20190513-business-case-v10-ld.pdf

World Organisation for Animal Health. (2024). Competency and Curriculum Guidelines for Community Animal Health Workers (p. 38). WOAH. https://doi.org/10.20506/woah.3535

World Organisation for Animal Health. (2025a, July). PVS Pathway. WOAH - World Organisation for Animal Health. https://www.woah.org/en/what-we-offer/improving-veterinary-services/pvs-pathway/

World Organisation for Animal Health. (2025b, July). Veterinary Workforce Development—WOAH. WOAH - World Organisation for Animal Health. https://www.woah.org/en/what-we-offer/improving-veterinary-services/pvs-pathway/veterinary-workforce-development/